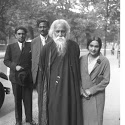

In our latest essay Dr. Shantanu Mukherjee (Frankfurt/Main) explains why Robindronath Thakur (Rabindranath Tagore) is a millennial figure in Bengal’s history. Wealthy and aristocratic, he was born in Calcutta in the second half of the 19th century. The mutiny in some native ranks of the British Army had just ended. After some gruesome excesses by both sides the uprising was finally crushed. The Crown, Queen Victoria at the time, formally took over direct control of Britain’s territories, no longer ready to rule by proxy through the high offices of the East India Company.

Thakur’s formal schooling was short. He was sent in his youth to England, came back, fell in love – if I see it right – with the attractive wife of one of his several brothers who seems to have returned the affection. He was married young. His marriage caused(?) his sister-in-law to end her life. Sixty long years thereafter, he is said to have desired on his deathbed to see a photo of his first love. In vain, I am told, because none could be salvaged. The two, I hope, have come together in heaven. If, then however with the assured snag of intimate encounters – the end of all cosmic tranquility, I am afraid.

Thakur wrote much, apparently without either weariness or pause. He covered every area of literature. In the early 1900s his fame reached the West – with the English translation of a slim volume of lyrics. Yeats, Pound and several others were fascinated, not the least due to their own urge towards things mystic, an urge whose final fulfilment they surely felt to have seen in Thakur’s poetry. Thakur came to Europe, met the people you meet and quickly became famous. Even the nice old gentleman who ran the heating at my first students’ hostel in Heidelberg enquired in detail, now that he knew me to be a Bengali, of the same tongue asThakur.

The crest of his fame coincided with his Nobel Prize in 1913. And his fame then evaporated equally quickly. Yeats, by now obviously bored, later commented, the language is mediocre, Tagore’s own translations stale – that, incidentally, was not much off the mark – and that Indians’ grip of English was unfirm.

Our title is meant to imply: he ought to be better known. Well, why so? His having won the Nobel prize is neither necessary nor sufficient claim to greatness, not even in places where his language, Bangla, is native to; let alone elsewhere. Consider the list of winners for literature in the last sixty years. How many could you name, how many have you read a line of? I should, I dare say, fail badly if called upon.

Greatness is not born in lists. There are no norms for becoming great. You know it when you see it. Like watching Maradona play football. It mercifully demands no definition. You know it when it grips the very sinews of your consciousness tight.

One mark of greatness though is that it is rare. You do not – and cannot – have it in abundance. The creator(s?) of the Mohabharot, the Iliad, the Old Testament, Dante, the Shakespeare of Lear and Macbeth, the Eliot of the Lyrics. And certainly others. Your choice will not completely coincide with mine; but most would agree on where the journey is going to. Thakur beyond doubts should be very much a part of this grand journey. But he is not. Why not?

1. BENGAL’S IRRELEVANCE

His Bengal, when it comes to military or economic strength, has long been quite insignificant in the affairs of states. And this sort of significance matters. The Bengali essayist Buddhodeb Bosu once remarked in frustration while at American unviersities that lorry-loads of papers were being regularly (the 1960s) produced on Yevtushenko and that no one was aware of Thakur. And it should be clear, why. The Great Cold War was raging (it was in fact the second World War. The Second was in fact the First, and the one called First was none, a European civil war of nations). I am quite sure Yevtushenko is today pretty much forgotten – notwithstanding his definite merits at damningly exposing Soviet Bolshevism’s genocidal atrocities visited upon Soviet Jews. I presume that instead a phalanx of Chinese literary figures is now being pampered in the USA.

2. ENGLISH TRANSLATION

Translations, the gateway to both transnational and sustained appreciation, have not, as far as I can see, served Thakur well. And, incidentally, he should better have put his fingers firmly away from translating his poetry. However, since my judgement is bound by my horizon, I leave it for You to judge.

3. MAGNUM OPUS

Thakur does not seem to have any. But greatness demands one. Were Shakespeare to have written a dozen Merry Wives of Windsor or Comedies of Errors, or Taming of Shrews, his claims upon posterity would have been thin. But he did not stop at those. He came up with his Macbeth. Thakur’s ‘Shyama’ for instance is to my mind of great and timeless beauty. But it is a musical, meant more to be heard than read. So too was Macbeth. But in Shyama the songs overwhelm us (heard), in Macbeth the awesome poetry of the play (read).

Thakur wrote a number of novels. None quite stands out, I believe. ‘Gora’, almost great, is spoilt by over-talking. Were Thakur to have published a selection (no collection) of his short stories in translations done by native speakers, my notes here would surely be superfluous.

4. SONGS

Thakur composed some two thousand songs. Many serene, majestic, ethereal, sublime. And the poetry of the text often outweighs the melody. And there is the rub. A Cantata from Bach or a Gregorian Chorale does carry words too. But what overwhelms is the tone, not the word. With Thakur it is often the other way round. This preponderance is equally legitimate. Only, that words are naturally bound to their native semantics. And so the world beyond is hardly accessible.

5. THE MYSTIQUE:

Thakur’s fame and its end were a great misunderstanding. That mystic-nebulous something, that lingering love seeking the proximity of God or Man or both, that dash of the Spiritual suspected in every corner – all this, I think, is not essential to great and timeless poetry. Remember that frustrated young man who once approached Malarme´, seeking solace at his having ‘grand ideas’ but being nevertheless bereft of great lyric? Upon this Malarme´ is supposed to have suggested consolation in his dictum: great poetry is not written with ideas, rather with words. And precisely hence is great poetry largely untranslatable

6. WORDS OVERFLOWING

Thakur seems never to have allowed himself a respite. Less would have been more – all the more so since he has countless jewels strewn amidst this over-abundance. And so many of his essays, plays and novels, dripping profundity, are a trifle tiring. I am confident, an extremely judicious way of pulling him out of his popularity-trough in the West, is a selection of his best lyrics and prose – short, to start with.

7. BLIND HOMAGE

Perpetual tributes and unbriddled canonization were not exactly fit to encourage critical reflexion in the poet.

8. EVIL

There is palpable absence of EVIL in Thakur. I am not quite as confident of my diagnosis here as in 1-7 above, because I am unsure whether literary greatness is indeed pale without the creation of EVIL. In the Mohabharot, in the Old Testament, in Lady Macbeth we see fathomless, inhuman, subterranean EVIL. I hesitate to claim the Iliad too has such. But then it has its remorselessness of Man and the Gods. And Thakur, with the possible exception of his drawings, stops way short of evoking grand EVIL that robs the soul, he stops way short of the Dantesque.

9. UNTRANSLATIBILITY

Thakur, great as he is, is supreme in his poetry. And the finest in and of poetry is nearly untranslatable precisely because it is not written with thoughts but with words (Cf. 4 and 5 above). And therefore again is great poetry largely untranslatable. Thakur wrote, more so in his later years, poetry slender, exquisite, resplendent in a cosmos beyond the transient; poetry though, that turns indifferent in translation. Here a few examples of my translation of Thakur (sorry, in German). The original, I am sure, counts among literature’s grandest jewels – but irrevocably suffers in translation:

(sudur kon nodir pare……)

An welch fernem Fluss

Bei welch undurchdringlichem Wald

In welch tiefem Dunkel

Überquerst Du

Lebensfreund, Gefährte, Oh Du meiner.

Heute, in der Sturmnacht,

Der Sturmnacht meiner Deiner.

( „ushar udoy somo onobogunthita, tumi okunthita..“)

„Unverschleiert, unverklemmt – wie der Sonnenaufgang.“

(dekhi tumi noto shire bunicho poshom…..)

Erblicke Dich, Kopf geneigt

Du strickst

Der Schöpfung unfehlbaren Frieden anerkennend.

Du strickst

Der Schöpfung unfehlbaren Frieden anerkennend.

(„dusshomoy“: jodio sondha…..)

Die Dämmerung naht, still, bar aller Umkehr

Der Gesang versiegt, alles so plötzlich stumm

Der Kosmos grenzlos, einsam öd und leer

Welch Erschöpfung hallt im Körper drum

Angst unsagbar, voller Erwartung, wortlos

Horizont lichtfern, verhüllt in schwarzem Schleier

Dennoch, Du Vogel, Lebensvogel, bloß

End nicht schon Dein Flügelschlages Dauer